ISOLATING THE EARLIEST HUMAN SPEECH

by

Charles Graves

The beginning of the process is to find those people who settled

somewhere at a very early time and were themselves isolated--for example in

the Amazon river region, in Australia and in areas which were not often visited

such as Siberia. Then, if available, study their vocabulary, in particular terms for

religious practices, family members, phenomena of nature etc. and compare these

terms with those of the other isolated people. Then we should verify if the same

terms are used among these isolated groups for the same objects or activities.

Finally, we should establish categories of these terms as to the precise relation

between the ‘subject’ and the ‘object’ which determined the syllables used in the

terms. And we should see if the categories and their syllables can be applied to

all languages, and note how are these applied in the various ethnic groups.

What was my experience in following each of these steps? We began with

our concept of human migrations at an early period--that human beings

originated in east Africa and by 150,000 BPE (before the present era) began to

enter the Near East heading towards, on the one hand, Europe, and on the other,

Central Asia. The very early humans crossed South Asia and ended in Australia;

others went into Siberia and reached the Pacific Ocean, and when conditions

allowed, crossed into the Americas. Those who entered Europe were the ‘old

Europeans’ in distinction from the ‘Indo-Europeans’ originating in Western Asia.

Also, humans began to populate all of Africa.

The anthropologists and ethnologists have studied the vocabularies of

these migrating peoples and some of the most interesting are the Siberian peoples

or the vocabularies of various Amerindian peoples (speaking nearly 300 different

languages). I compared the Siberian terms with those of the Amerindians,

especially concerning religion, nature and family life. The results of the

ethnologists’ language research was very valuable.

These comparisons of terminology appeared in my three books published

by Brockmeyer Press in Bochum (Germany) in the 1990s (Bochum Publications

in Evolutionary Cultural Semiotics)(1). I was particularly interested in Siberian

and Central Asian language terminology in relation to two main macrofamilies

(of language) established by the Russian linguists Sergei Starostin, Vitaly

Shevoroshkin, Oleg Mudrac, the Serbian scholar Vladislav Illich-Svitich and

some American linguists including John Bengtson and Joseph Greenberg. The two

main macrofamilies--‘Nostratic’ (of Illich-Svitich) and ‘Sino-Caucasian’ (of

Starostin) were presented for American and other scholars at the First

International Interdisciplinary Symposium on Language and Prehistory, Ann

Arbor, University of Michigan) 8-12 November 1988 (2) The two categories of

macrofamilies presupposed a common proto-language circa. 15,000 BPE. Some

Central Asian, Siberian or Amerindian languages fell into the ‘Nostratic’

category – others were ‘Sino-Caucasian’. The scholars could also envision a

separate Siberian-Amerindian category. The two main categories appeared

valuable so that if a language had features of both Nostratic and Sino-Caucasian

one might believe it was developed earlier than either of those which securely fit

into one or the other categories.

Some ancient languages were found among isolated people who not only

showed a pre-Nostratic-Sino Caucasian split but also were equivalent to other

very early languages and here I speak of languages such as Ainu (Hokkaido,

Japan); Australian Aboriginal, or in the Amazon region Machiguenka or

Yanonami. The noun and verb term near-equivalents among these groups raised

the issue of whether there was an original human language. When these common

human terms were found it was the moment to classify the terms according to

their meaning for the speaker. Were certain syllables used in all these primitive

languages meaning the same thing for each? If some syllables were used among

these languages for the same meaning, then an original proto-language could be

found. Then it would be useful to isolate each syllable according to its use in this

early language. For this we listed the syllables under one of eleven categories

which one could imagine covered all relations between a subject (a human) and an

object (in the human’s environment). So the 214 syllables were isolated--each

representing a category of meaning. In all world languages this syllable would

mean the same thing (3).

In my three books in the series Only One Human Language (IVER

publications) (4) the 214 proto-syllables have been tested as to their relevance to

the world’s languages. Languages of the nineteenth-twentieth centuries in various

regions have been subjected to the test in these three volumes. The final volume on

African and Near Eastern languages confirmed the thesis of the 214 original

syllables and their categories. The implication is that early homo sapiens found that

the syllables were so useful that through much use, they were ‘coded’ in the human

brain, and also transmitted in embryo to the DNA of children.

The procedure of establishing these syllables was, in my opinion, related

to the search for food. As with other primates, food was a basic necessity for daily

survival. And so, the mouth was involved in the making of the early syllables not

only because it was required to make the sounds but also to create ‘meaning’ vis

à vis the object encountered. The ‘object’ was thought to be entering the mouth

(as well as the consciousness) and because it ‘stimulated the mouth’, the mouth

‘spoke’ the syllables in return. The important question as to why homo sapiens

speaks while other primates utter sounds but do not, in fact, speak, is based upon

this aspect of the mouth being involved existentially in the subject-object

relation (5).

But these sounds of the mouth in relation to an object were important in

many ways, because they became ‘social, communal’ and homo sapiens received

these sounds as ‘meaningful’ vis à vis what the relation really was between subject

and object. It was logical that neural circuits were solidified through repetition of

syllables that conveyed meaning and that, the society repeating these syllables,

such neuronal contacts were continued to be made in order to speak these syllables.

These neuronal relations then became ‘coded’ or became permanently-creating

aspects of the DNA of homo sapiens vis à vis parts of the brain controlling the

muscular organs of speech. This may explain why the language of homo sapiens

was very different from that of gorillas or chimpanzees. Through this coding

influencing the DNA structure of the brain and mouth and their interaction, such

DNA could be passed on to children who would--in principle-- be able to make the

same sounds vis à vis the subject-object relations as their parents, and the syllables

would fall into the same categories as they had done for the parents.

In other words, it was the search for food and the eating of it that brought

about the origin of language, and language had the aspect of a mouth-brain (and

later a brain-mouth) component. Apparently, the mouth was the earlier origin of

speech rather than the brain. Thus, language was not created by the mind absorbing

and reflecting upon the environment, but by the mouth providing sound syllables

which eventually through wide community use, became essential for survival.

The sounds began to stimulate the brain through neural circuits which enabled

repetitions of these sounds and, as time went on, neural circuits attained a higher

level of organization --each sound being related to its ‘meaning’ (its raison d’être

as a special ‘subject-object’ essence).

Early humans did not ‘tell’ their mouths to say such and such because they

‘decided’ to make sounds vis à vis such and such object. On the contrary. it

appears that the sounds of the mouth and its parts reacting to an object, and

repeated again and again in the community, began to be received by the brain as

elements which should be integrated into the neuronal structure--these being the

‘fittest’ for human communication, and thus sounds (syllables)--because they

were essential--became ‘encoded’ in the neuron-logical connections of the brain.

These phenomena were occurring no doubt before homo sapiens moved

out of Africa.

Was language thus ‘innate? No, it was developed in reaction to the

external objects, but repetition and widespread use, and ‘survival of the fittest’ of

these connections made a certain number of sound-syllables ‘innate’, i.e. part of

the brain neurology which became more and more developed and, through DNA

could be transmitted to children. The brain and mouth became accustomed to

certain syllables which had meaning rather widely, and the repetition of these

created a permanent set of syllables each having a particular meaning. Humans

could add to the basic syllables but could not remove them because their mouthing

had become an integral part of the brain’s working. Thus, the same syllables were

used not only in ancient Australia but also in the Amazon river basin.

And our studies of the various languages has shown that the 214 syllables I

have presented have infiltrated the noun and verb content of every language.

To summarize our argument: the brain was not highly developed in early

homo sapiens--it would be possible that while foraging for food, the mouth

utterances could, if repeated a multiplicity of times, and reinforced by spreading

within the society, begin to affect the neurons in the slowly developing brain and,

shape those neuronal circuits which control the organs of the mouth. Then

these neuronal connections could cause modifications in the brain mass, and if the

syllable continued to be spoken for the same subject-object relations, the

modifications could be strengthened to the extent where these could be

transmitted in the DNA to descendants.

Various peoples can be shown to have general DNA links and the oldest

populations have the same DNA as David Reich has shown about Australian

Aboriginals and some Amazonian Amerindians (6). So early homo sapiens’

speech could also be the same for the Australians and certain Amazonians. But

we have learned in our research which syllables made up such early speech, and

what each syllable meant (i.e. the category to which it belongs). Thus, in a way,

this proves that there was only one original language since the DNA structure of

these far-distant peoples is the same and their language terminology is the

same. These equivalences cannot certainly be simply coincidental.

Why this happened can only, we believe, be explained by the fact that

basic speech possibilities are related to heredity, as much as to environment. If

speech is related to heredity it must be transmitted through the DNA and neuron

arrangements related to speech must have been hereditary at a certain era and

since. If the shape of a bodily organ can be hereditary why not also the primitive

neuron arrangement in the brain--that which controls speech? For example, in the

human brain, fundamental neuro-muscular circuitry necessary for speech is

operative by the end of the first year of life; however, acquisition of multiple

syllables, words and sentences requires many more years and is under the influence

of both heredity and a nurturing human environment. Thus, neurons and their laws

of passage would be the same as other laws of hereditary passage from one

generation to another.

But, as with bodily parts which are hereditary, so also would be early brain

functions--these were ‘kick-started’ by the fact that early humans reacted to

objects by their mouths and the sounds they made were registered in the brain

and later controlled by the brain

Mouth movements were at first spontaneous but became ‘coded’ through

the ‘survival of the fittest’ syllables. The syllables ‘fit’ the subject-object relation

and early homo sapiens began to believe in these syllables and use them for the

purpose for which they were originally created. If these syllables were not the

original ones and if they were not arranged in categories which were consistent

(as we have proposed), then why can we see them and their categories again and

again--meaning the same thing--in all the language terminology we have

researched?

The Categories of the Syllables

The essential part of my research is the isolation of the 214 syllables

divided into eleven categories. These seem to be the original syllables spoken by

early homo sapiens to be enunciated by the mouth vis à vis what they as subjects

encountering objects wanted to say about these objects.

It is obvious that, in order to give a name (syllables) to certain objects,

humans gave it a name depending upon the ethnicity and the language spoken. For

this reason the word for an equivalent object is different in different human

languages (as de Saussure had underlined). It appears then that it is the culture, or

the ethnic group, which decides which syllable to use for such and such an

‘object’. But if the ‘oldest’ languages are compared i.e. the old most isolated

terminologies are compared (as we have done with Australian Aboriginal, some

Andean or Amazonian terms as well as with the four ‘control groups’ (Indo-

European, Burushaski, Japanese and Australian Aboriginal), it appears that the

syllables used to describe the same ‘object’ fall into the same categories each time.

This corresponds to what David Reich found comparing the DNA of some of these

particular groups.

They are the same because they were the descendants of the earliest homo

sapiens who had begun their migrations out across South Asia or Siberia.

These earliest languages and their terminology fully conform to our list of

syllables.

The way we arrived at the list was a comparison of four kinds of

terminologies which were, in a sense, quite separate both geographically and in

terminology. They were: Indo-European; Burushaski (a ‘Sino-Caucasian’

language spoken in the Karakoram Pass area of South Asia and similar to Chechen,

Basque, Proto-Chinese, Navajo); Japanese (a mix of Siberian Languages such as

Yukaghir, Evenki, Ainu); and Australian Aboriginal. I believed these represented

the major world languages, the ‘Sino-Caucasian’ also including Thai and

Kampuchean; the Yukaghir being close to Kashmiri and Malay etc.

It appears that one could isolate how each of these terminologies used the

same syllables to explain the same subject-object relationship. That does not

mean that the terms in the four groups, in each case, used the same syllables or

words, but that each group used one of a series of syllables which we have

attributed to a certain category. The fact of the existence of the use of same

categories was the proof of our thesis, rather than the equivalences of the

syllables or terms themselves – which was obviously quite different in each

case.

So, the proof of the validity of the thesis of 214 proto-syllables was simply

to see if a term in one of the four above-mentioned languages included as

principal syllable a syllable which fell into the same category of syllables as

that of the syllable used for the same term in one of the other languages. In

fact in most cases the same syllable was used. In my three volumes of Only

One Human Language I have tested the 214 proto-syllables in many

world languages and found that these proto-syllables have been used in the

same way in forming terms (mainly nouns and verbs) everywhere without

exception.

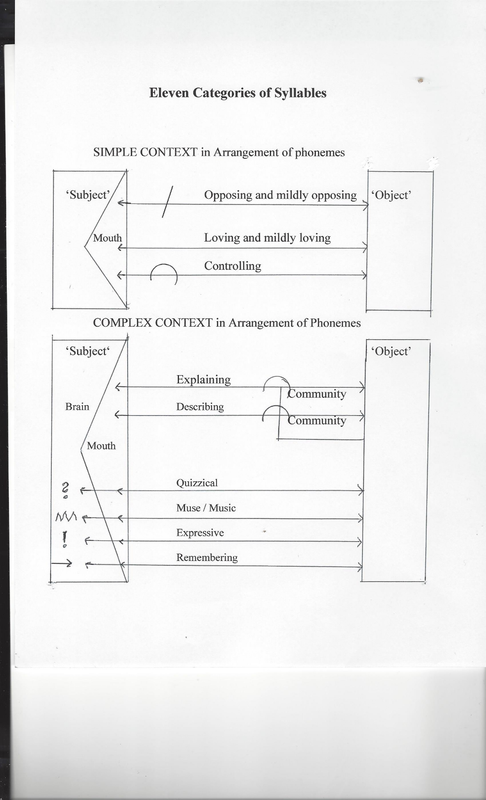

How did we determine the eleven categories? And how did early homo

sapiens use the hypothetically-arrived-at categories we have determined? It

was only by a common sense approach we asked ourselves by which type of

relations did a subject (homo sapiens) relate to an object in his

environment? Common sense arrived at primitive reactions: love or mild love;

opposition or mild opposition--the most primitive of subject-object relations.

Secondly the subject may see the object as something or someone to control.

Thirdly, the object could be seen neutrally as to be explained or to be

described. The four other categories include a quizzical one, i.e. the subject

does not know what to think about the object. Or a subject could be affected

by the object so that a musical or at least a musing aspect to the relation

occurred in the brain. Again, an object could provoke in the same homo

sapiens’ brain an expressive reaction--a crying out or showing strong emotion.

Finally, we could not omit to include another important reaction in the subject:

remembering. The brain recalls, through repetitive experiences, that it has

encountered this object previously. Or, remembering what happened previously, it

believes it will encounter this object once again.

As we can see in the chart (pp.18-23) there are various syllables in each

category. So in our three volumes Only One Human Language we have submitted

many nouns and verbs of each language--spoken even today--and we have found

that the syllables used in each term fall into the category we have established for

that syllable.

Besides the four types of language used in the original survey to determine

the proto-syllables, we investigated Siberian languages, Ainu, Amerindian

languages; Kashmiri, Burushaski and languages of the Karakoram region, Malay

as well as Thai and Kampuchean; Chinese; Pacific languages; A multitude of

Amerindian languages ending in the Amazon region; Near Eastern language

vocabularies such as Aramaic, Hebrew, Arabic: terms for ancient Greek and

Egyptian deities; Kabylie language terminology, proto-Bantu as well as two

Bantu languages: Swahili and Zulu. Terminology in these languages conformed

to my system of syllables in 95% of cases. Any exceptions were explained in the

text. Some words could, according to the specificity of the ethnic or national

group, fail to fall into its normal category of meaning and was termed by us as

‘ambiguous’. This did not obviate our theory, but in all cases proved that our

proto-syllables’ language structure was being questioned somewhat because of

divergent ethnic beliefs, while not being rejected.

We have a possibility to test the hypothesis with a term from a language;

Usually the term can be broken down into two or three syllables, Using the chart of

syllables we can see if the syllables used in the terms fit the categories holding

that or these syllables in the list. We could make comparisons of a hundred terms

of any one language as its vocabulary is given even today and see if each syllable

conforms to the category which, in my theory, the syllable should belong i.e. if

the category gives the proper meaning. For example, often domestic animals fit

into the controlling category when the subject regards them, or some

excitement-provoking terms would at least contain one expressive syllable.

Sounds or music-related terms would include a muse/musical syllable.

Readers may well ask the question--how can a professional theologian

arrive at conclusions on the realm of linguistics? My studies have been mainly in

the study of the history of religious thought--my doctoral thesis was on the

religious philosophy of the Russian theologian Sergius Bulgakov 1870-1945 (7,

10).

But the use of Russian language was very helpful for my books published

in Bochum on religious practices in Siberia, Central Asia and for the

Amerindians--where the religious terminology was found to be parallel in both

sides of the Pacific Ocean.

After attending a conference in New Delhi on the peoples of the

Karakoram region in India and its political and ethnic issues (8) I once again took

up my research on the origin of languages after I found a surprise parallel

between Kashmiri terms and Malay terms. So, I became a linguist in the sense I

was trying to prove a hypothesis related to linguistics. Afterwards I made a study

of the working of the brain, which could use to explain my theory, and made a

quick review of some of the major linguistic theories today.

Nobel Prize winner the Prof. Eric Kandel has taught us to inquire: ‘in what sense – biologically-speaking – were syllables encoded in the brains of early homo sapiens? (9) Kandel has presented in his book the physiological basis of certain aspects of memory and the unconscious which provides much material for thought. ‘Consciousness’ involves sensory neurons, motor neurons, mouth muscles (for speech) and several other brain parts for the production of syllables. Have linguists been able to describe the neural pathways leading to the pronunciation of these syllables and which of the brain’s areas are involved? What is the role of ‘genes’ in the determining which syllables are used for each of the eleven different categories I have described? Is it true that, as shown in the diagram on p. 24 that certain subject-object experiences seem to ‘penetrate’ the brain (beyond the mouth) e.g. remembering, emotion, music etc.? How are these experiences circulated in the brain and how do their neuronal connections pass through various areas of the brain, and which areas are these?

Notes:

- Graves, C. (1994). Proto-Religions in Central Asia Universitätsverlag Dr.

Norbert Brockmeyer, Bochum (BPX 34) 223 pp.; (1995) The Asian Origins of

Amerindian Religions, Bochum (BPX 37) 268 pp.; (1997) Old Eurasian and

Amerindian Onomastics, Bochum (BPX 38) 254 pp.

- For example: Vitaly Shevoroshkin, Ed. (1989) Reconstructing Languages

And Cultures Universitätsverlag Dr. Norbert Brockmeyer. Bochum (Bochum

Publications in Evolutionary Cultural Semiotics (BPX 20) 176 pp.; Vitaly

Shevoroshkin, ed. (1991) Dene-Sino-Caucasian Languages, Bochum (BPX 32)

264 pp.

- ‘Proto-syllables’ mean two or three vowels or consonants grouped together.

A ‘phoneme’ would be another word for these. ’Terminology’ means the sense of

the main syllable used in a word (noun, verb, adjective) and, in our system, can be

compared with similar essences (i.e. ‘terminologies’) in various languages.

- Only One Human Language. The Unique Language of Homo Sapiens

(2016). Iver Publications, 393 pp.; Asia-Amerindia Language Comparisons. Only

One Human Language (2018,). vol. II; Iver Publications 411 pp.; The Speech of

Early Homo Sapiens. Only One Human Language, (2019). vol. III; Iver

Publications, 344 pp. (listed on Amazon.com)

- Explanation of the above phrase “These sounds of the mouth in relation to

the object are important in themselves…” The sounds (syllables) emitted by the

mouth have meaning in themselves. Here we approach what Beneviste has

inferred: that original human language expresses some primitive ‘ideas’. Beneviste

hoped to find these proto-ideas in studying early language. On the other hand, C.G.

Jung has presented his ‘archetypes’ found in dreams i.e. certain primitive

‘creaturely’ essences which are part of a collective unconscious. Our eleven

‘categories’ of the proto-syllables could be seen along this line, perhaps. For

example, the ‘philosophy’ of the category of loving or mildly loving could be

related somehow to an archetype of optimists; the category of controlling be

related to farmers; the category of muse/music related to poets; the category of

remembering related to researchers. So, these proto-syllables within their

categories have a kind of ‘philosophical’ aspect. Thus Beneviste was proposing

something valuable. However, his method could not establish the proto-

syllables themselves.

(6) Reich, D. (2018). Who We Are And How We Got Here. Ancient DNA and

the New Science of the Human Past New York; Pantheon Books 335 pp.

(7) Graves. C. (1972). The Holy Spirit in the Theology of Sergius Bulgakov

(University of Basel D. Theol. Thesis 1972), 190 pp.

(8) Graves, C. (2013). ‘Origins of Peoples of the Karakoram Himalaya’. In:

Himalayan and Central Asian Studies, New Delhi vol. 17, No. 1 January-March,

pp. 3-18.

(9) Kandel, Eric R., winner of the Nobel Prize. In Search of Memory. The Emergence of a New Science of Mind. New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company, see especially pp. 282-3, 308-9.

(10) My language abilities began with Latin studies and continued with French at University and. German language studies for the doctorate. Language skills in Russian were completed at Oxford with a tutor and after this I learned the Japanese terms with my wife. In 1972 I studied Finno-Ugric culture as well as Russian at Turku and Helsinki in Finland during one summer. All these elements were used in my three books published in the series Evolutionary Cultural Semiotics in Bochum University press (1990s).

From my mother’s side I have elements of haplogroup ‘G’ in my DNA which is attributed to the Alans / Ossetians, a Scythian group as Georges Dumézil has categorized it, which may explain my propensity for Russian studies.

My work as secretary-general of Interfaith International 1993-2019 has introduced me to many cultures and terminologies including some Amerindian languages, Indo-Iranian languages, Burushaski, Baluch, Sindhi and Kashmiri,

CHART OF 214 SYLLABLES IN ELEVEN CATEGORIES

Syllables beginning with a consonant:

Opposing: kl, no, ne, ni

Mildly opposing: fre, go, gi, ja, pa, pl, sw, vu, vl, za, zl

Loving: chu, do, di, fa, ha, zhi, kh, ji, li, ma, nu, ro,

so, ta, vo, vi

Mildly loving: bo, bi, bl, cha, cho, gu, gh, zhu, ku, lo, re,

So, sy, te, tw, wo, wi, zu

Explaining: ba, br, che, da, du, de, dw, fe, ga, ghe, ka, le,

na, pl, sa, wu

Controlling : bu, chi, dr, fi, ko, ki, me, pu, sl, sr, tr, wr

Quizzical : be, fo, mo, qua, ru

Muse-Music: fu, ja, mu, su, yo

Describing: fl, ga, ge, gr, gl, kr, lo, lu, li, mi, no, pa, po,

pl, pr, pi, rta, se, si, to, tu

Expressing : ri, yi, zo

Remembering : he, hi, hu, ki, ko, pe, wo, wu

Syllables beginning with a vowel:

Opposing: er, ig, op

Mildly opposing: ag

Loving: am, em, af, ip, ez, iz, eu, iu, oi, ui, uo, oqu

Mildly loving: eh, uh, ao, ou

Controlling: im, um, at, et, ot, as, uk, al, el, il, ol, an, en,

in, ed, id, ih, uz

Explaining: if

Quizzical: om, is, od, oh, az, oz, ei

Muse-Music: or, on, og, ug, ao, ou, uqu

Describing: it, ir, os, ek, ok, eb, uf, ep, eo, io, ia, oe, aqu,

equ, iqu

Expressing: ar, ek, ob, eg, ah, ap, ai, ie, ou

Remembering: et, ur, ae

Another version of the 214 proto-syllables

There will be more than 214 examples, since some are included in two separate categories (see below).

Preliminary analysis of these syllables and the phonemes involved

In my list the juxtaposition of the phonemes is related existentially to the ‘gestalt’ of the particular category (one out of eleven of them).

Regarding the pronouncement of the phonemes in this article, and in my books on Only One Human Language, the vowels (i, e, a) are to be pronounced (in English) more like bit, bet, bat than like bite, beet, or bait. For the vowels o, u they are to be pronounced like bought / boat and like but / boot.

Ai is pronounced like the vowels of bat/bit

Ie is pronounced like bit/bet

Re is pronounced like the vowels in rest/rain

Og is pronounced like phonemes in ox/go

Ug is pronounced like under/go

Uqu is pronounced like ung; Equ is pronounced like eng

Opposing and mildly opposing syllables

er, fre

ig

kl, pl, vl, zl

ig, ag, go, gi

ni, no, ne

pa, pl

vu, vl

za, zl

ja

Opposing: rejection is shown by either first or last phoneme whereby mouth rejects outside influence

Mildly opposing: Opposition is shown by the failure of the last phenome to eliminate the earlier ‘mild’ phoneme. This ‘mild’ is shown by the combination of last and first phoneme

Loving and mildly loving syllables

am, em, ma, eh

am, af, fa, zha, ma, ta, ao

do, ro, so, vo, ou, cho, lo, so, wo

di, ji, li, vi, sy, wi

ez, iz, zha, zhi, eh

ui, uo, oqu, nu, zu

zha, zhu, chu, cha, cho, zhu

eh, uh

bo, bi, bl

gu, gh

ta, te

Loving: The last phoneme is ‘open’ (it ‘receives’) or the last phoneme (am, em, af, ip, ez, iz) is ‘inclusive’.

Mildly loving: The first phoneme is ‘mildly’ non-opposing, or a bit opposing (gh, gu (m.loving) with go gi (m. opposing); so, sy (m. loving) with sw (mildly opposing); zu (m. loving) with za, zl (m. opposing).

Controlling syllables

im, um, me, ed, id

at, et, it, ol

an, en, in, un

ed, id

id, ih

dr, sr, tr, wr

chi, fi, ki

bu

Controlling: the phonemes ‘elide’ like the remembering category. But their eliding is with ‘strength’, not simply with openness

Explaining syllables

da, du, de, dw

if, fe, pi

ba, da, ga, ka, na, sa

dw, wu

ghe, ga, ka

che, de, fe, ghe, le

Explaining: The second phoneme is ‘inclusive’, ‘wraps around’ and ‘lingers’ whereas the controlling syllables don’t ‘linger’ in order to explain. Cf. controlling pu with explaining pl.

Describing syllables

it, ir, io, ia, iqu,

li, ti, pi

ek, ok, aqu, equ, iqu

eb, ep, equ, eo

ga, ge, gr, gl, aqu

gr, kr, pr, rta, vr, wr

fl, lu, li, pl, sl

wa, wu, we, wr

to tu, ti

ya, yu, ye, ia, oe

eo, io, ia, oe

eo, no, po, to

pa, po, pl, pr, pi, eb, ep

Describing: is like explaining. Their second phoneme is ‘mildly inclusive’ Cf. controlling al, el, il, ol with describing lo, lu, li; Cf. controlling pu with describing pa, po, pl, pr; Cf. remembering pe with describing pa, po, pl, pr; Cf. remembering et with describing to, tu. Describing has much nasal elements (aqu, equ, iqu as well as ek, ok, eb, ep, io, ia) which may indicate ‘negative describing’ e.g. ng

Muse/Music syllables

or, on, og, ou, yo

fu, ru, mu, su,

ug, uqu, qua, ru

Muse / Music: the phonemes ‘elide’ together but (in comparison with remembering) include an ‘added emphasis’

Expressing syllables

ek, eg

ar, ah, ap, ai

ai,. Ie, ri, yi

ob, oa, zo

Expressing; the phonemes, both first and last, either ‘go to the top of the oral cavity’ (ri, yi, zo, ar, ek, eg) or they show much openness (ah, ap, ai, ie, ou). These aspects show a certain emotion

Remembering syllables

he, hi, hu

ki, ko

wo, wu, ur

et, ae

pe

Quizzical syllables

om, od, ob, oz

is, az

fo, mo

ja, az

Remembering and Quizzical:in remembering the phonemes ‘elide’ whereas in quizzical the phonemes ‘oppose’ each other (one is ‘closed’ the other is ‘open’). Remembering shows wide openness especially in the last phoneme which ‘lingers’. With quizzical the second phoneme does not ‘linger’, but ‘opposes’.

Syllables used in two different categories

wu (in expl. and remem.)

et (in contr. and remem.)

ki, ko (in contr. and remem.)

pa (in oppos. and descr.)

ou (in loving and muse/music)

Therefore, the significance of the relation between the two phonemes of each syllable and the nature of the second phoneme defines the co- incidence between the syllable and the ‘gestalt’ of the subject-object relation it represents. We could, of course, try to see how the shape of the mouth producing the two phonemes may show certain patterns for each double phoneme (i.e. syllable), and how these shapes may coincide with certain ‘gestalts’ related to the subject-object relation concerned.

Photograph: ‘rock painting’ in Australia photographed by Graeme Churchard, Bristol (UK)